![]()

13.3.2026 | 2026年3月13日 星期五

![]()

13.3.2026 | 2026年3月13日 星期五

从“葵纹”到模块化符号

早在很久前,陈旭东就一直在对“葵纹”进行探索。在建筑设计的研究中,他发现中国传统园林的设计中,在窗棂或地砖的纹路方面,都可以看到许多类似“葵纹”的图案或符号。但是,在西方的建筑中就很少见到这种“葵纹”。他认为图案是介于具体与抽象之间的符号,有时它象征着某种具体事物,有时又很模糊,在这种似是而非的状态中,“图案”就具有了一种非常大的可能性,它包含一种文化信息。将“葵纹”通过参数化的方式令图案进行变化,由此而创作出“葵凳”。

初见“葵凳”,这把椅子或许会让你产生疑惑,你很难分清楚这把椅子究竟属于西方或传统东方设计语言。这把椅子由六边形的平面组成,每一个平面相互叠加形成一个看似像向日葵般的模块。这种处理方式会让人想到几何学中的“分形”法则,如同曼德博集合一般,一个模块可以无限衍生,堆叠出更庞大的模块。“西方视角看中国的文字就是一种模块化的符号,你看每个字都由横竖撇捺等部首偏旁组成,可以说模块化是中国文化的一种特色。”陈旭东说。通过对“葵纹”模块化的研究为方向,在探寻中西方文化差异的同时,意图寻找一种能够解码不同设计语言差异的方式,“符号模块化”的尝试正是陈旭东的一种全新思路。

(摘自《诠释》,2015.04)

-----------------------------

MPTF: What is your main design focus at DAtrans?

Chen: We try to find new strategies in China’s complicated and quickly changing society. The main challenge is to try to find a “new way” – a new way in relation to what we have done before but also in relation to the western way of doing things. We are looking for a mix of traditional Chinese and western international style. In this way, we are constantly trying to find our own way: developing our own mythology to create our projects.

MPTF: Would you say that your work is widely influenced by having studied in Berlin and seen other cities? Because presumably it is strongly influenced by being in an international city like Shanghai?

Chen: Yes of course. We live in a society of communication networks. All of the information that we receive is from the internet, a shared open source. It is difficult to say ‘I am not very influenced by the global situation’ but ironically that also means it can be quite difficult to find your own identity. The notion of “identity” is currently not a topic for a lot of people in China, but for me it is very important. How can you find your identity in our rapidly changing cultural and historical context… and interpret this into a project. Of course, we communicate with people from all over the world all the time, so we are always inter-related. As an architect, one’s job must be to be independent but also connected to your environment, friends and the one’s surroundings.

MPTF: In Berlin you also studied philosophy and art. Does that expertise play any role in your designs?

Chen: I always say that architecture is architecture… and that philosophy and art are separate disciplines. For example, we all like different things (maybe you like music and I like literature) meaning that it would be really difficult for you to try to write some literature, while I try to compose a song. What I mean is that if you are thinking of art you will not really be thinking about architecture. For me it is always separate.

Firstly, philosophy itself is a learning process: of understanding the world, which really helps to inform architecture. I really liked philosophy in university, exploring the works of philosophers like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. And our generation – at the time of ‘opening up’ to the world – needed new and fresh ideas. Ideas from western philosophy were, and are, an important part of that learning process. At university you have the desire to learn and hopefully that learning never really stops.

Secondly, architecture is always related to art. We learnt painting from a very young age and this becomes the base of architecture. But contemporary art is completely different; there are performances, installations, and digital art and more. Contemporary art is always developing and this inspired me to keep thinking and learning. Art helps creativity, it helps you to be independent. In fact, these two approaches help you to develop a way of thinking, which is not only useful for architecture but in everything. Most importantly it teaches you to dare to do things.

MPTF: The way you deal with old buildings is to change them rather than demolishing them. How does this suit the development of the city as more people need living space and old buildings occupy a large amount of space?

Chen: Old buildings are relatively cheap especially for young people and companies. If you have not got much money, then it is often cheaper and easier to rent a renovated or recycled building. So it is a very practical alternative. Jane Jacobs’ “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” is very important for urban design in that it reminds us that cities should keep some old buildings for charm, for function, for memory and for efficiency.

MPTF: How do you identify which should be preserved and which demolished?

Chen: Of course there are historical buildings and it is the role of the historian to identify which buildings are much more valuable over time.

MPTF: Do you suggest to keep the facade and rebuild the inside: to improve the living conditions of the older structures, to help contemporary living standards?

Chen: I think architects need to focus on reality. Sometimes architects don’t – sometimes they find that they can’t – make decisions. I think this question is often not on an architectural level. It is relates to investment, and also economics and politics.

MPTF: Do you not think architecture is mixed with the political and economic levels?

Chen: Of course.

MPTF: Should an architect try to challenge such decisions then, or just accept the situation however much he or she might disagree?

Chen: It is important to find the proper client. If they are not interested in good quality or historic value maybe you shouldn’t work with them. You may get money but you will never be satisfied with what you create. In this circumstance, it is probably better to say ‘no’ from the beginning.

MPTF: Not many architects could say they can pick clients. Is that not a bit unrealistic?

Chen: Architects are very lucky if someone is willing to spend so much money on a project and to give you free rein in what you want to do. But actually, why should someone trust you? If a client gives you RMB100 million and you create something that only furthers your own dreams, then I think that you are too egotistical.

I really like the interpretation by Mies van der Rohe. He said that in the beginning you are young and you start with architecture as a student. “First you have to learn something; then you can go out and do it.” In other words, as you learn and become experienced you create buildings. But these are only building – an object – you should stull not consider yourself to be an artist. Buildings become architecture through the combination of thought and actions: between an idea and the cultural conditions. Only afterwards – when you are finally not student but a career architect – does artistic work have the potential to arise. Always (maybe) in the future you can become a master who always creates artistic works.

MPTF: Do you always complete research for each project? And how do you go about it?

Chen: I think there are three different ways to do research:

Firstly, if you are focused on one particular typology, then you should explore similar case studies, buildings and projects and find specific regulations and guidelines for these particular projects. Then you collect all these experiences and incorporate it in your new project.

Secondly, if you do a general building, it is undoubtedly more like urban project, so you should become really objective; you should keep your distance in your research.

Finally, for a one-off, client-specific project, it is quite open, and therefore this allows you to make an artistic intervention perhaps… something that you should develop from a story specific to the client; one where you can get inspiration from the client’s own personal lifestyle and hobbies.

MPTF: On that point, do you have a preference? o you think it’s good for architects to have a certain style or should they design to be specific for the people?

Chen: As an architect, you always face to this issue: with style or without style. Sometime, the style can be visible and invisible: visible form and invisible method. I prefer a developmental process that is much more about method and strategy, rather than form. In the process of interpreting the results of the research and the analysis, maybe the form will keep the same identity as the initial idea, or maybe it will change. I never know. So for me, I always say that before I experiment with the design, I never know the stylistic result.

MPTF: So maybe you shouldn’t go in with any pre-conceived ideas?

Chen: Yeah, you should be a detective. Allowing yourself to be part of the design development usually means that you will enjoy the process. If you know the end, how can you really enjoy it? So my assistants always angry because I am always changing things until the last second (laughs).

MPTF: So do your designs start with your own ideas or do you use a collaborative approach between architects and engineers, for example? In other words, how do you generate ideas?

Chen: In our office, we often like to cooperate with different people, engineers, artists, designers, etc… and also with poets.

MPTF: Poet? How can they help?

Chen: Just by participating in the discussion is useful and interesting. They come, and talk with us and often help us by offering new, improved, different suggestions. Why not?

MPTF: So do you think the architect is no longer the leader?

Chen: I really like the metaphor by a professor of my school in Berlin. He always say that the architect should be a coordinator, not a leader. Personally, I think that everyone is equal. If everyone is professional about it, then you can coordinate the intelligent experience of everyone into the project, meaning that the project becomes most successful. Undoubtedly, the situation in China is a little different to Europe, because in Europe there are so many experienced design professionals, but in China, we are still in the stage where every discipline is learning and developing. So it’ is quite difficult to find people and to set up a stable relationship where genuine cooperation can take place. But we still try to do that. So China, at the moment, has more foreign companies and institutions than local ones but the situation in China is changing. Not too long ago, the client thought ‘why I should pay design fees’ and so they just paid the construction costs (and builders’ fees). Interior designers were worst hit early on in the development of a design sensitivity in China and there was never any interior design fee; their fee was always included in the construction budget. Slowly – but thankfully – more and more clients and developers have begun to realize that design is also important. It is now a good time to be an architect where intelligence and creativity are increasingly valued commodities.

相关链接:

Interview with Chen Xudong of DAtrans, Shanghai, MFT,19.01.14

-----------------------------

在理性掛帅的建筑界,西方工业文明的精确理性往往是形塑一栋建筑的绝对条件,但如何让建筑拥有自己的灵魂?建筑师陈旭东引用哲学家牟宗三所言「中西贯通」,一言蔽之地说明了东方有机和空灵的自然思想,是支持一栋建筑的重要内涵。

來到上海,「M50」就像一個神祕的密碼,吸引著眾人前往朝聖。這裡是中國最著名的藝術特區,70年代老舊廠房轉型成個性藝術思潮的發生地,其幕後重要推手就是德默營造創辦人、建築師陳旭東。

建築是人格思維的呈現在德國學建築同時也修習哲學的陳旭東,擁有一份中國傳統文人的情懷,自承愛翻古書、練書法、遊園林、喜歡徽州村落,有一種陶淵明式的山水情結。對傳統理想人格那份溫良恭儉讓的眷戀,成了陳旭東在建築上的重要語彙。

無論是杭州西湖江南會的傳統形制配上精緻木工藝術、徐州鼓樓民生服務中心的簡練中蘊藏巧思,或是M50的工業感混搭SOHO風,乍看之下這些作品風格多元而廣泛,但事實上核心皆取自中國傳統「合院」模式,並以中國理想建築「外觀簡潔而富有內涵」為精神,試圖透過現代手法探索內外互動的空間關係。

無法割捨的東方思維讓他所領導的德默營造更加關注於建築內部的營造和層次感,例如使用穿孔的金屬板來表現透明、層次和肌理的關係,在精準、簡潔的美學架構下,德默營造的作品就像一位謙謙君子,能最大限度地容納周遭環境的多樣性與複雜性,成為真正融入社會文化的公共建築。

启动城市的热点

「追求建筑的原创性,应以不破坏公共城市景观形象以及误导公众消费和生活习惯为前提。」陈旭东特别推崇建筑需蕴含一种朴素而有节制的建筑风格和语言,以应对当下追求奢华和炫富的商业文化。面对现今中国上下对西方舶来品不假思索、全盘接受的态度,更让他反思中国所拥有的传统,如农耕立国的历史,近代工厂的产业文明等。尤其在看到台湾建筑师谢英俊、黄声远及文化人黄永松等人,长期以独立立场和个性化眼光关注台湾社区与乡村建设,以及台中市府订定文化与国际化作为都市发展目标,更让陈旭东对中国建筑的未来有了更多想象。

如果城市是会呼吸的人体,那建筑肯定是其中的一个细胞;一个细胞很难直接产生影响,但只要成组织,器官,最后绝对可以撼动全身。因此,德默营造的作品就像是启动城市的热点,结合艺术与文化思维,慢慢朝向有机城市的概念发展。

(摘自 台湾《La Vie》,2013.No108)

-----------------------------

为上海的第一处创意产业聚集地莫干山路M50做好了园区规划,旅德归来的建筑师陈旭东决定出本书,拿这具体项目做线索,有凭有据地讲一讲城市空间地修缮与营造。之后成就的书,叫做《二手摩登》,不光书名摩登,长相也是个性十足——封面上,施了淡粉,开本上,也很别出心裁,粉嫩扁厚的一本,赢了书的内容,和砖砌屋造楼的砖头有些神似。

把纸头做成砖头的样子,这是陈旭东特意为之的。在他眼里,书和建筑本身就有一些通融之处——“记载一个时代成就的不是书就是建筑。”而“造一个建筑就像写本书,不管好坏,它都会在立在那里。”而更有意思的是,书和建筑为了给自己挣得“立在那里”资格,有时候还会闹点别扭,陈旭东眼中,雨果所写的《巴黎圣母院》中,就隐有这一主题——“圣母院最后被烧掉了,纸质的书打败了石头做的书。”

“文学杀死建筑”,这是雨果写出的意见。雨果所处的时代,由印刷术勃兴而带生的出版业正在欧洲迅猛发展。为书籍的前途高声喝彩,甚至不惜拿建筑的消损来做映衬,该算是写书人顺时而生的喜乐吧。

现今,宣言书式的建筑已显寡少,这倒是应了雨果语言的一半,然而新兴媒介对传统出版的挑战,却也如纸头烧掉石头一样绝情,这份惨淡,该是雨果绝难料见的。若将雨果请来当下,使他看到手中的恢弘大著,竟就不敌网上断章残句的现实,不知这位爱书人又会生发何种喟叹。兴许,他会让共沐风雨的建筑和书携手勉励,为这二者共著一段爱恨情仇吧。

巧的是,在陈旭东多年来的实践里,就有三件与“书”相关的案例。那三个项目,分别是今年年初开始正式运转的“广东美术馆人文图书馆”,曾在M50园区经营过一段时间的“东八书仓”(Timezone8);以及早先为瑞典首都斯德哥尔摩Asplund图书馆提交的扩建方案。在如何为书打造庇护所,或者搭建新天地的问题上,做过研究与实践的陈旭东,逐渐形成了自己的见解。

三个方案,都要在新环境里为纸质书和爱书人创制空间,彼此之间便有些可见可感的共通点,而其背后所承载的人文思索,更是一脉相承。不如回溯到这一脉络的最初,从为Asplund图书馆所做的扩建方案说起。

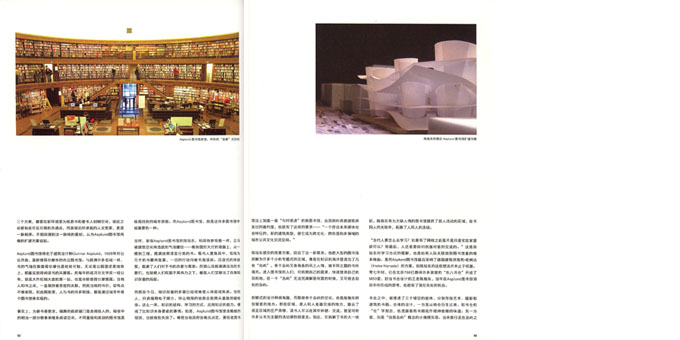

Asplund图书馆得名于建筑设计师Gunnar Asplund,1928年对公众开放,是斯德哥尔摩市的市立图书馆。与欧洲许多名城一样,书的气场在斯德哥尔摩也是处处可触,无论是公园里还是地铁上,都能见到得闲读书的风雅客。而每年的诺贝尔文学奖一经公布,获奖大作旺销大卖的第一站,也是非斯德哥尔摩莫属。当地人和书之间,一直保持着亲密的关联,然而当地的书价,却有点不够亲民,如此局势里,人与书的许多联接,都是通过城市中各个图书馆来实现的。

事实上,为使书香更浓,瑞典的政府部门是舍得投入的,税收中的相当一部分都拿来维系阅读空间,不同量级和类别的图书馆是极易找到的城市景致。而Asplund图书馆,就是这许多图书馆中极重要的一种。

当时,亲临Asplund图书馆的陈旭东,和其他参观者一样,立马被建筑空间所造就的气场攫住——眼前圆形大厅的墙面上,从一楼到三楼,摆满按照语言分类的书。看书人置身其中,视线为万千的书册所笼罩,一切的行动均被书海浸润。沉浸式的体验里,载满了人们对于书的热爱与尊崇。而如山岳般满满当当的书册们,也驱使人们叹服于其伟力之下,催促人们察觉出了自身知识存量的局促。

然而在今日,知识存量的多寡已经很难使人得意或焦虑。任何人,只消擅用电子媒介,排山倒海的信息总能劈头盖脸的砸给你。这么一来,知识的结构,学习的方式,应用知识的能力,便成了比知识本身要紧的事情。如是,Asplund图书馆里圣殿般的视效,也就有些失效了。难怪当地政府会作出决定,要在老图书馆边上加盖一座“与时俱进”的新图书馆,由政府向各路建筑师发出的邀约里,也就有了这样的要求——“一个符合未来媒体社会特征的,新的建筑类型,使它成为跨文化、跨阶层和多领域的城市公共文化交流空间。”

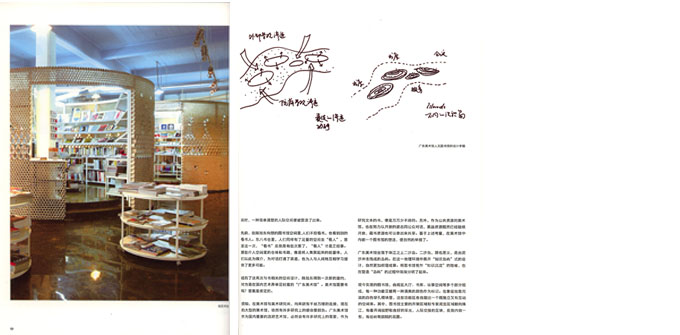

陈旭东提交的竞赛方案,回应了这一新需求,他把大型的图书馆拆解为许多个小的专题式的区域,像是在知识海洋里造出几处“岛屿”,各个岛屿又各有各的风土人情,被不同主题的书所填充。进入图书馆的人们,可依照自己的需求,快速登录自己的目的地,在一个“岛屿”无法完满解答所需的时候,又可绕去别处的岛屿。

拆解式的设计师很有趣,而联络各个岛屿的空间,也是陈旭东特别留意的地方。那些区域,是人和人直面交接的地方,撤去了阅览区域的庄严肃穆,读书人可以在其中休憩、交流,甚至可将许多以书为主题的活动挪到那里去。如此,在拆解了书的大一统后,陈旭东有为欠缺人情的图书馆提供了容人活动的区域,在书同人的关联外,拓展了人同人的连结。

“当代人要怎么去学习?如果有了网络之后是不是只是宅在家里就可以?到最后,人还是要回归到面对面的交流的。”这是陈旭东对学习方式的理解,也是他将人际关联放到图书馆里的根本缘由。虽然Asplund图书馆最后采纳了德国建筑师海克·哈纳达(Heike Hanada)的方案,但陈旭东在当时的思考并未止于纸面。零七年时,已在北京798已攒得许多美誉的“东八书仓”开进了M50里,担当书仓设计的正是陈旭东,当年在Asplund图书馆项目中形成的思考,也就有了落在实处的机会。

书仓之中,被摆进了三个镂空的舱体,分别存放艺术、摄影和建筑的书籍。仓体的设计,一方面从粮仓衍生过来,和书仓的“仓”字契合,也透露着将书籍视作精神食粮的味道;另一方面,则是“信息岛屿”概念的小规模实现。当来客行走在岛屿之间时,一种简单清楚的人际空间便被营造了出来。

先前,在陈旭东构想的图书馆空间里,人们不但看书,也看到别的看书人。东八书仓里,人们同样有了足量的空间去“看人”,甚至这一次,“看书”反倒是有些次要了,“看人”才是正经事。那些介入空间里的仓体和书籍,像是将人集聚起来的能量体,人们以此为媒介,为对话打通了渠道,也为人与人间地互相学习提供了更多可能。

经历了这两次与书相关的空间设计,陈旭东得到一次新的邀约,对方是在国内艺术界举足轻重的“广东美术馆”。美术馆需要书吗?答案是肯定的。

须知,在美术馆与美术研究间,向来就有千丝万缕的连接,而现在的大型的美术馆,依然有许多研究上的使命要担负。广东美术馆作为与国内重要的政府艺术馆,必然会有许多研究上的需要,作为研究文本的书,便是万万少不得的。另外,作为公共资源的美术馆,也在努力以开放的姿态同公众对话,展品资源既然已经陆续开放,藏书资源也可以拿出来共享。基于上述考量,在美术馆中内嵌一个图书馆的想法,便自然的举措了。

广东美术馆坐落于珠江之上二沙岛。二沙岛,顾名思义,是由泥沙冲击而成的岛屿。这一地理环境中展开使“知识岛屿”的设计,自然是更加顺理成章。将图书馆作为“知识沉淀”的隐喻,也在营造“岛屿”的过程中渐渐分明了起来。

现今实现的图书馆,由阅览大厅、书库、议事空间等多个部分组成,每一种功能区都用一种清爽的颜色作为标记。在象征信息河流的白色穿孔模块里,这些功能区各自凝出一个既彼此独立又有所互动的空间来。其中,图书馆主要的开架区和专家阅览朝向珠江,有着开阔视野和良好采光,人际交接的区块,反倒内敛的一些,有些岭南庭院的氛围。

(摘自 《O2氧气生活》,2010.12)

-----------------------------

“上海是一种精神状态。这座城市比她的房子和事实的总和还要多,是一种带有风格、立场和感知的存在物。当北京还以诸如房屋的数目和体量这样的物理特征来定义的时候,上海已更多地和时间相关联了,流动感、不稳定、短暂性、幻想、幻觉、迷醉感、幻灭感。上海,一只不停旋转的万花筒。”

——时间如潮,拉梅施·库马·比斯瓦思

在流动着,并将持续流动的上海,“M50”或许也只是诸多历史切片之一。它与被标记作“莫干山50号”的这一片土地,在某个时空坐标上相遇,发生了一些事件。

在此之前很长一段时间里,“莫干山50号”有它自己的复述者与复述方式。19世纪末到20世纪30年代初期,是上海民族工业大发展的时期。以苏州河和黄浦江为轴线,莫干山路两侧成为上海工业生产带中民族工业最为集中,规模最大的一处工厂区,见证了民族资本的面粉工业和纺织印染工业的兴起和发展。1937年,信和纱厂、信孚印染厂、信义机器厂组成当时上海最大的协作生产集团。其中信和纱厂就是今天的莫干山50号,50年代改为纺织厂,60年代改为毛纺织厂,随后变为全民所有制,直至1999年停产。

这段复述未免有些絮叨,意象也不够清晰。城市需要断言,用以在语速极快的这段历史中,抓住它的复述者,并在这种复述的复述中留存下去,彰显自身。于是作为创意产业集聚区的“M50”出现在2005年,带着它的国际口音和历史光环。即使实际上艺术家在更早的时候就已经来到这里。2000年,作为第一个正式入驻的艺术家,薛松将这个离家近、面积大、价格便宜的地方租作工作空间。随后劳伦斯、王兴伟、张恩利、丁乙……等陆续到来。

从时间逻辑上看,寻求创作场地的艺术家们对这里的标示要远早于“M50”,他们显然也不是受了某种历史感的策动而集聚到这里,否则日后“M50”的出台就成了一场预谋。只不过,在“莫干山50号”漫长、有些散漫的复述中,偶然谈及的某个与“创意”相仿的字词,被需要断言的城市捕捉到了,贴作标签,拿出来给人看。由此,或许可以说,“M50”本身,也是“莫干山50号”的二手,就如“摩登”是“现代”的二手。

2009年的今天,M50成为莫干山50号的代名词四年之后,在此活动着的艺术家、设计师和文化人士,和2005年相比已经有了很大改变。可以预见的是,“M50”这个词条将会被不断替换,更新。

全新思路。

“从2005年初萌生对莫干山50号改造的初步设想开始,至今三年的时间里,关于如何进行现状更新和潜力挖掘的讨论,在业主、设计师、用户和公众之间一直都未停止过。在与业主、社区代表形成一种互动机制之中,起初理想化的概念,经历了剧烈的碰撞和耗散,最后被部分地实施……”

——缓慢的循环,二手摩登:M50/莫干山50号的城市营造,德默营造+陈旭东

相比于同类项目,由德默营造担当的M50改造与其说是创新性的设计,还不如说是某种有意识的干涉。

“改造策略”(M50设计纲要·总则)——整个区域的改造将是一个持续的、有计划的和分步进行的过程。在改造过程中,所有的创作、展览和活动将如期进行,因此在持续的转型和改造的过程中,必须确保现有驻户工作的连续性。

某种占卜式的规划——我试图用这个不专业的词汇来概括我对这份改造设计原则的总体印象。通过一种连续的、提问式的、有意识的对话,令M50的未来逐渐展现在它自己的话语中,从多个潜在的未来事件之间选择一种连线方式,构成从今以后的M50。人们司空见惯的终极蓝图在这里似乎缺席了——“M50将来会是这样、这样或这样”——我从来没有听陈旭东这样说过。相反,“这里将来会是怎样?”的质疑与不确定始终引导关于这里的城市研究,成为“M50”的内涵之一。

批判性的更新——在这里,改造的意识进入之前,首先摒弃了某种追求所谓进步的过于积极的态度,以及随意丢弃不合时宜的事物的所谓时尚的习惯。通过适量引入另一种秩序,这里原先有些冷寂的生态被激活,随后发生了一些适或不适的反应,这些反应逐渐积累,二手的城市形态也相应显露。

一手面前,总是保持二手的克制,自省和敏感,这种气质将M50从其他同类那里区分出来。

“这个厂区跟整个上海城市空间的关联,跟历史的关联,而且跟上海这个城市在上个世纪30年代文化艺术创造性的领域里所扮演的角色有关。我们现在的艺术设计文学和当时有非常大的关联。那个时候是很先进的意识形式。当时我们想有没有可能在世纪交替之时,在厂区被改造的时候,通过物质空间的改造给这种思想,这种创造历程提供一种新的空间。这是我认为最最有意思的点,所以激发起我们从04年到08年的行为艺术。”

——摩登·城市·二手摩登,尤伦斯当代艺术中心,陈旭东

30年代的上海城市肌理中,并存有一手空间、二手空间。一手的原生态空间和老城厢空间,与二手的移植来的租界空间有着截然不同的肌理。前者自由生发、内向生长,后者规整划分、向外蔓延。20世纪末的上海城市中,二手的空间发生了分化。原先移植来的租界空间经过时间洗练,成为上海特色的城市肌理。其间,以M50为代表的旧厂房改造与再利用,成为一种创意产业园区开发的典型模式,移植到其他城市。二手的二手成了原型,变为一手。与此同时,新的二手空间又在这里扎根,城市中央商务区,大型社区,城市中心广场,滨水景区,全球化城市呼喊出资本的潮动。都是二手,又各异其趣。

时隔七十载,“摩登”这一上世纪30年代上海都市文化的要义卷土重来。或许是文化基因自身的作用力使然,30年代关于“现代性”的先进意识,七十年后的今天再次赋予城市空间以生命力。具有时间、空间双重连续性的M50,可以引发人们对更多可能性的想象与思考,从而集体营造出具有活力的场所。从另一个角度看,M50在多大程度上与莫干山50号有着重叠的命运,目前还无法预测。这种对空间的持续利用和改造还可能带M51,N50,也可能什么也不是。无论何种,在这里展开的一系列研究、实践和探讨,都将成为未来考证M50的切实材料。

-----------------------------

An alumnus of the Swiss firm Herzog & deMeuron, architect Chen Xudong helped design China’s spectacular Beijing National Stadium for next year’s Summer Olympics. But as principal of the Shanghai firm DAtrans, the 35-year-old is also among a generation of young Chinese designers who are shaping an emerging homegrown architecture that demonstrates a native sensibility without resorting to cliché. Consider Chen’s strikingly humble scheme for the new Time¬zone 8 bookstore in Shanghai.

Built on a tight budget, the 2,153-square-foot store occupies a former workshop in 50 Moganshan Road, the converted factory complex that has become Shanghai’s hotbed of contemporary art. To organize the space, Chen came up with a solution that’s at once straightforward and complex: three cylindrical display partitions comprising perhaps 20,000 cross sections of PVC pipes. Given that the architect eschews superficial references—“I don’t believe in putting pagoda tops on modern buildings,” he says—it would be a mistake to compare their honeycomb structure to traditional Chinese latticework screens (tempting as it may be). Instead, Chen sees his silo like forms as firmly rooted in Modernism—though the pipes, which are of two different diameters, have been arranged in random patterns by the workmen who assembled them. “We just designed the parameters,” he says. “The workers could explore the flexibility within those parameters, which is a traditional Chinese way of construction.”

Built on a tight budget, the 2,153-square-foot store occupies a former workshop in 50 Moganshan Road, the converted factory complex that has become Shanghai’s hotbed of contemporary art. To organize the space, Chen came up with a solution that’s at once straightforward and complex: three cylindrical display partitions comprising perhaps 20,000 cross sections of PVC pipes. Given that the architect eschews superficial references—“I don’t believe in putting pagoda tops on modern buildings,” he says—it would be a mistake to compare their honeycomb structure to traditional Chinese latticework screens (tempting as it may be). Instead, Chen sees his silo like forms as firmly rooted in Modernism—though the pipes, which are of two ¬different diameters, have been arranged in random patterns by the workmen who assembled them. “We just designed the parameters,” he says. “The workers could explore the flexibility within those par¬ameters, which is a traditional Chinese way of construction.”。

Although he didn’t realize it at the time, Chen had channeled Chinese architecture’s historic underpinnings, a menu of forms and typologies that had long been standardized yet was open to subsequent interpretation (without the impositions of architects, who didn’t exist in the Western sense until the twentieth century). This flexibility within a prescribed system lies at the heart of Chen’s partitions, each of which has a different diameter, while their placement and openwork surfaces blur one’s sense of being either outside or within them—much like the traditional Chinese courtyard typology. In other words, “it’s about borrowing traditional ideas—not traditional buildings,” says Chen, who adds that for him the influence is more intuitive than conscious.

The rest of the space was left mostly raw, but Chen did allow for another notable flourish: a sequence of painted overscale bar codes by the hip Shanghai graphic designer JiJi that demarcate the bookstore by subject area. “They’re an ironic statement about the over¬design of the commercial environment,” Chen says. “I prefer a sense of improvisation, which maybe reflects China’s current condition.”

-----------------------------